10

Static Build Pipelines

| 10.1 Mill Build Pipelines | 183 |

| 10.2 Mill Modules | 187 |

| 10.3 Revisiting our Static Site Script | 191 |

| 10.4 Conversion to a Mill Build Pipeline | 191 |

| 10.5 Extending our Static Site Pipeline | 195 |

import mill.*

def srcs = Task.Source("src")

def concat = Task:

os.write(Task.dest / "concat.txt", os.list(srcs().path).map(os.read(_)))

PathRef(Task.dest / "concat.txt")

Snippet 10.1: the definition of a simple Mill build pipeline

Build pipelines are a common pattern, where you have files and assets you want to process but want to do so efficiently, incrementally, and in parallel. This usually means only re-processing files when they change, and re-using the already processed assets as much as possible. Whether you are compiling Scala, minifying Javascript, or compressing tarballs, many of these file-processing workflows can be slow. Parallelizing these workflows and avoiding unnecessary work can greatly speed up your development cycle.

This chapter will walk through how to use the Mill build tool to set up these build pipelines, and demonstrate the advantages of a build pipeline over a naive build script. We will take the simple static site generator we wrote in Chapter 9: Self-Contained Scala Scripts and convert it into an efficient build pipeline that can incrementally update the static site as you make changes to the sources. We will be using the Mill build tool in several of the projects later in the book, starting with Chapter 14: Simple Web and API Servers.

10.1 Mill Build Pipelines

10.1.1 Defining a Build Pipeline

To introduce the core concepts in Mill, we'll first look at a trivial Mill build that takes files in a source folder and concatenates them together:

build.mill10.2.scalaimportmill.*defsrcs=Task.Source("src")defconcat=Task:os.write(Task.dest/"concat.txt",os.list(srcs().path).map(os.read(_)))PathRef(Task.dest/"concat.txt")

You can read this snippet as follows:

-

This

build.millfile defines one source foldersrcsand one downstream taskconcat. -

We make use of

srcsin the body ofconcatvia thesrcs()syntax, which tells Mill thatconcatdepends onsrcsand makes the value ofsrcsavailable toconcat. -

Inside

concat, we list thesrc/folder, read all the files, and concatenate their contents into a single fileconcat.txt. -

The final

concat.txtfile is wrapped in aPathRef, which tells Mill that we care not just about the name of the file, but also its contents.

This results in the following simple dependency graph

10.1.1.1 Tasks

The Mill build tool is built around the concept of tasks. Tasks are the nodes within the build graph, and represent individual steps that make up your build pipeline.

Every task you define via the def foo = Task: syntax gives you the

following things for free:

- It is made available for you to run from the command line via

./mill foo - The return value of the

Task:block is made printable via./mill show foo - It automatically evaluates any necessary upstream tasks, before its own

Task:block evaluates - It automatically caches the computed result on disk, and only re-evaluates when its inputs change

In general, this helps automate a lot of the tedious book-keeping that is normally needed when writing incremental build scripts. Rather than spending your time writing command-line argument parsers or hand-rolling a caching and invalidation strategy, Mill handles all that for you and allows you to focus on the logical structure of your build.

10.1.1.2 Task Destination Folders

Note that concat.txt is created within the concat task's

destination folder Task.dest. Every task has its own destination folder, named

after the fully-qualified path to the task (in this case, out/concat.dest/).

This means that we do not have to worry about concat's files being

accidentally over-written by other tasks.

In general, any Mill task should only create and modify files within its own

Task.dest, to avoid collisions and interference with other tasks. The contents

of Task.dest are deleted each time before the task evaluates,

(and only evaluates when changes are detected), ensuring that the

task always starts each evaluation with a fresh destination folder and isn't

affected by the outcome of previous evaluations.

10.1.2 Using Your Build Pipeline

Assuming you already have a ./mill script set up, we can then create a src/ folder

with some files inside:

$ mkdir src

$ echo "hear me moo" > src/iamcow.txt

$ echo "hello world" > src/hello.txt

10.3.bashWe can now build the concat task, ask Mill to print the path to its

output file, and inspect its contents:

$ ./mill concat

$ ./mill show concat

"ref:fd0201e7:/Users/lihaoyi/test/out/concat.dest/concat.txt"

$ cat out/concat.dest/concat.txt

hear me moo

hello world

10.4.bashMill re-uses output files whenever possible: calling ./mill concat repeatedly returns the

already generated concat.txt file. However, if we change the contents of the

srcs by adding a new file to the folder, Mill automatically re-builds

concat.txt to take the new input into account:

$ echo "twice as much as you" > src/iweigh.txt

$ ./mill concat

$ cat out/concat.dest/concat.txt

hear me moo

twice as much as you

hello world

10.5.scala10.1.3 Non-linear Build Pipelines

While our build pipeline above only has one set of sources and one task, we

can also define more complex builds. For example, here is an example build with

2 source folders (src/ and resources/) and 3 tasks (concat, compress

and zipped):

build.mill10.6.scalaimportmill.*defsrcs=Task.Source("src")+defresources=Task.Source("resources")defconcat=Task:...+defcompress=Task:+forp<-os.list(resources().path)do+valcopied=Task.dest/p.relativeTo(resources().path)+os.copy(p,copied)+os.call(cmd=("gzip",copied))++PathRef(Task.dest)++defzipped=Task:+valtemp=Task.dest/"temp"+os.makeDir(temp)+os.copy(concat().path,temp/"concat.txt")++forp<-os.list(compress().path)do+os.copy(p,temp/p.relativeTo(compress().path))++os.call(cmd=("zip","-r",Task.dest/"out.zip","."),cwd=temp)+PathRef(Task.dest/"out.zip")+

In addition to concatenating files, we also gzip compress the contents of our

resources/ folder. We then take the concatenated sources and compressed

resources and zip them all up into a final out.zip file:

Given files in both srcs/ and resources/:

| |

We can run ./mill zipped and see the expected concat.txt and *.gz files in

the output out.zip:

$ ./mill show zipped

"ref:a3771625:/Users/lihaoyi/test/out/zipped.dest/out.zip"

$ unzip -l out/zipped.dest/out.zip

Archive: out/zipped.dest/out.zip

Length Date Time Name

--------- ---------- ----- ----

35 11-30-2019 13:10 foo.md.gz

45 11-30-2019 13:10 concat.txt

40 11-30-2019 13:10 thing.py.gz

10.9.bash10.1.4 Incremental Re-Computation

As shown earlier, out.zip is re-used as long as none of the inputs (src/ and

resources/) change. However, because our pipeline has two branches, the

concat and compress tasks are independent: concat is only re-generated

if the src/ folder changes:

And the compress task is only re-generated if the resources/ folder

changes:

Since compress and concat do not depend on each other, Mill will

automatically run them in parallel.

While in these examples our tasks all returned PathRefs to files or

folders, you can also define tasks that return any data type

compatible with the uPickle library we went through in Chapter 8: JSON and Binary Data Serialization.

10.2 Mill Modules

Mill also supports the concept of modules. You can use modules to define repetitive sets of build tasks.

It is very common for certain sets of tasks to be duplicated within your

build: perhaps for every folder of source files, you want to compile them, lint

them, package them, test them, and publish them. By defining a trait that

extends Module, you can apply the same set of tasks to different folders on

disk, making it easy to manage the build for larger and more complex projects.

Here we are taking the set of srcs/resources and

concat/compress/zipped tasks we defined earlier and wrapping them in a

trait FooModule so they can be re-used:

build.mill10.10.scalaimportmill.*+traitFooModuleextendsModule:defsrcs=Task.Source("src")defresources=Task.Source("resources")defconcat=Task:...defcompress=Task:...defzipped=Task:...++objectbarextendsFooModule+objectquxextendsFooModule

object bar and object qux extend trait FooModule, and have source paths

(accessible via the inherited moduleDir property) of bar/ and qux/ respectively.

The srcs and resources definitions above thus point to the following folders:

bar/src/bar/resources/qux/src/qux/resources/

You can ask Mill to list out the possible tasks for you to build via

./mill resolve __ (that's two _s in a row):

$ ./mill resolve __

bar.compress

bar.concat

bar.resources

bar.srcs

bar.zipped

qux.compress

qux.concat

qux.resources

qux.srcs

qux.zipped

10.11.bashAny of the tasks above can be built from the command line, e.g. via

$ mkdir -p bar/src bar/resources

$ echo "Hello" > bar/src/hello.txt; echo "World" > bar/src/world.txt

$ ./mill show bar.zipped

"ref:efdf1f3c:/Users/lihaoyi/test/out/bar/zipped.dest/out.zip"

$ unzip out/bar/zipped.dest/out.zip

Archive: out/bar/zipped.dest/out.zip

extracting: concat.txt

$ cat concat.txt

Hello

World

10.12.bash10.2.1 Nested Modules

Modules can also be nested to form arbitrary hierarchies:

build.mill10.13.scalaimportmill.*traitFooModuleextendsModule:defsrcs=Task.Source("src")defconcat=Task:os.write(Task.dest/"concat.txt",os.list(srcs().path).map(os.read(_)))PathRef(Task.dest/"concat.txt")objectbarextendsFooModule:objectinner1extendsFooModuleobjectinner2extendsFooModuleobjectwrapperextendsModule:objectquxextendsFooModule

Here we have four FooModules: bar, bar.inner1, bar.inner2, and

wrapper.qux. This exposes the following source folders and tasks:

|

Source Folders

|

Tasks

|

Note that wrapper itself is a Module but not a FooModule, and thus does

not itself define a wrapper/src/ source folder or a wrapper.concat task.

In general, every object in your module hierarchy needs to inherit from

Module, although you can inherit from a custom subtype of FooModule if you

want them to have some common tasks already defined.

The moduleDir made available within each module differs: while in the

top-level build pipelines we saw earlier moduleDir was always equal to

os.pwd, within a module the moduleDir reflects the module path, e.g.

the moduleDir of bar is bar/, the moduleDir of wrapper.qux

is wrapper/qux/, and so on.

10.2.2 Cross Modules

The last basic concept we will look at is cross modules. These are most useful when the number or layout of modules in your build isn't fixed, but can vary based on e.g. the files on the filesystem:

build.mill10.14.scalaimportmill.*importmillBuildCtx.api.valitems=BuildCtx.watchValue{os.list(BuildCtx.workspaceRoot/"foo").map(_.last)}objectfooextendsCross[FooModule](items)traitFooModuleextendsCross.Module[String]:defmoduleDir=super.moduleDir/crossValuedefsrcs=Task.Source("src")defconcat=Task:os.write(Task.dest/"concat.txt",os.list(srcs().path).map(os.read(_)))PathRef(Task.dest/"concat.txt")

Here, we define a cross module foo that takes a set of items found by

listing the sub-folders in foo/. This set of items is dynamic, and can

change if the folders on disk change, without needing to update the build.mill

file for every change.

Note the BuildCtx.watchValue call; this is necessary to tell Mill to take note

in case the number or layout of modules within the foo/ folder changes.

Without it, we would need to restart the Mill process using ./mill shutdown to

pick up changes in how many entries the cross-module contains.

The Cross class that foo inherits is a Mill builtin, that automatically

generates a set of Mill modules corresponding to the items we passed in.

10.2.3 Modules Based on Folder Layout

Typically, a cross module has the same moduleDir as an ordinary module, but in the example above

it is overwritten to consider the crossValue as part of the path, giving each module

a unique srcs directory.

As written, given a filesystem layout on the left, it results in the source

folders and concat tasks on the right:

|

sources

tasks |

If we then add a new source folder via mkdir -p, Mill picks up the additional

module and concat target:

$ mkdir -p foo/thing/src

$ ./mill resolve __.concat

foo[bar].concat

foo[qux].concat

foo[thing].concat

10.17.bash10.3 Revisiting our Static Site Script

We have now gone through the basics of how to use Mill to define simple asset

pipelines to incrementally perform operations on a small set of files. Next, we

will return to the Blog.scala static site script we wrote in Chapter 9, and

see how we can use these techniques to make it incremental: to only re-build the

pages of the static site whose inputs changed since the last time they were

built.

While Blog.scala works fine in small cases, there is one big limitation: the

entire script runs every time. Even if you only change one blog post's .md

file, every file will need to be re-processed. This is wasteful, and can be slow

as the number of blog posts grows. On a large blog, re-processing every post can

take upwards of 20-30 seconds: a long time to wait every time you tweak some

wording!

It is possible to manually keep track of which .md file was converted into

which .html file, and thus avoid re-processing .md files unnecessarily.

However, this kind of book-keeping is tedious and easy to get wrong. Luckily,

this is the kind of book-keeping and incremental re-processing that Mill is good

at!

10.4 Conversion to a Mill Build Pipeline

We will now walk through a step by step conversion of this Blog.scala script file

into a Mill build.mill. First, we must rename Blog.scala into build.mill to

convert it into a Mill build pipeline and add the import mill.* declaration:

Blog.scala -> build.mill10.18.scala+importmill.*importscalatagsText..all.*

Second, since we can rely on Mill invalidating and deleting stale files and

folders as they fall out of date, we no longer need the os.remove.all and

os.makeDir.all calls:

build.mill10.19.scala-os.remove.all(os.pwd/"out")-os.makeDir.all(os.pwd/"out/post")

We will also remove the def main method and publishing code for now. mill build pipelines

use a different syntax for taking command-line arguments than Scala files do,

and porting this functionality to our Mill build pipeline is

left as an exercise at the end of the chapter.

build.mill10.20.scala-defmain(targetGitRepo:String="")=...--iftargetGitRepo!=""then-os.call(cmd=("git","init"),cwd=os.pwd/"out")-os.call(cmd=("git","add","-A"),cwd=os.pwd/"out")-os.call(cmd=("git","commit","-am","."),cwd=os.pwd/"out")-os.call(cmd=("git","push",targetGitRepo,"head","-f"),cwd=os.pwd/"out")

Lastly, we need to wrap the computation of postInfo inside a mill.api.BuildCtx.watchValue

call, to ensure that changes to postInfo are detected by ./mill --watch:

build.mill10.21.scala-valpostInfo=os-.list(os.pwd/"post")-.map:p=>-vals"$prefix-$suffix.md"=p.last-(prefix,suffix,p)-.sortBy(_(0).toInt)+importmillBuildCtx.api.+valpostInfo=BuildCtx.watchValue:+os.list(BuildCtx.workspaceRoot/"post")+.map:p=>+vals"$prefix-$suffix.md"=p.last+(prefix,suffix,p)+.sortBy(_(0).toInt)

Note also how we replaced os.pwd with BuildCtx.workspaceRoot. That is necessary as the Mill's

os.pwd may not always point at the root folder of your project.

10.4.1 For-Loop to Cross Modules

Third, we convert the for-loop that we previously used to iterate over the

files in the postInfo list, and convert it into a cross module. That will

allow every blog post's .md file to be processed, invalidated, and

re-processed independently only if the original .md file changes:

build.mill10.22.scala-for(_,suffix,path)<-postInfodo+objectpostextendsCross[PostModule](postInfo.map(_(0)))+traitPostModuleextendsCross.Module[String]:+defnumber=crossValue+valSome((_,suffix,markdownPath))=postInfo.find(_(0)==number)+defsrcPath=Task.Source(markdownPath)+defrender=Task:valparser=org.commonmark.parser.Parser.builder().build()-valdocument=parser.parse(os.read(srcPath))+valdocument=parser.parse(os.read(srcPath().path))valrenderer=org.commonmark.renderer.html.HtmlRenderer.builder().build()valoutput=renderer.render(document)os.write(-os.pwd/"out/post"/mdNameToHtml(suffix),+Task.dest/mdNameToHtml(suffix),doctype("html")(...))+PathRef(Task.dest/mdNameToHtml(suffix))

Note how the items in the Cross[](...) declaration are the numbers corresponding

to each post in our postInfo list. For each item, we define a source path

which is the source file itself, as well as a def render task which is a

PathRef to the generated HTML. In the conversion from a hardcoded script to a

Mill build pipeline, all the hardcoded references writing files os.pwd / "out"

have been replaced by the Task.dest of each task.

10.4.2 An Index Page Task

Fourth, we wrap the generation of the index.html file into a task as well:

build.mill10.23.scala+deflinks=Task.Input{postInfo.map(_(1))}++defindex=Task:os.write(-os.pwd/"out/index.html",+Task.dest/"index.html",doctype("html")(html(head(bootstrapCss),body(h1("Blog"),-for(_,suffix,_)<-postInfodo+forsuffix<-links()doyieldh2(a(href:=("post/"+mdNameToHtml(suffix)))(suffix))))))+PathRef(Task.dest/"index.html")

Note that we need to define a def links task that is a Task.Input: this tells

Mill that the contents of the postInfo.map expression may change (since it

depends on the files present on disk) and to make sure to re-evaluate it every

time to check for changes. Again, the hardcoded references to os.pwd / "out"

have been replaced by the Task.dest of the individual task.

10.4.3 Arranging Files For Distribution

Lastly, we need to aggregate all our individual posts and the index.html file

into a single task, which we will call dist (short for "distribution"):

build.mill10.24.scala+valposts=Task.sequence(postInfo.map(_(0)).map(post(_).render))++defdist=Task:+forpost<-posts()do+os.copy(post.path,Task.dest/"post"/post.path.last,createFolders=true)++os.copy(index().path,Task.dest/"index.html")++PathRef(Task.dest)

This is necessary because while previously we created the HTML files for the

individual posts and index "in place", now they are each created in separate

Task.dest folders assigned by Mill so they can be separately invalidated and

re-generated. Thus we need to copy them all into a single folder that we can

open locally in the browser or upload to a static site host.

Note that we need to use the helper method Task.sequence to turn the

Seq[T[PathRef]] into a T[Seq[PathRef]] for us to use in def dist.

10.4.4 Using Your Static Build Pipeline

We now have a static site pipeline with the following shape:

We can now take the same set of posts we used earlier, and build them into a

static website using ./mill. Note that the output is now in the

out/dist.dest/ folder, which is the Task.dest folder for the dist task.

$ find post -type f

post/1 - My First Post.md

post/3 - My Third Post.md

post/2 - My Second Post.md

$ ./mill show dist

"ref:b33a3c95:/Users/lihaoyi/Github/blog/out/dist.dest"

$ find out/dist.dest -type f

out/dist.dest/index.html

out/dist.dest/post/my-first-post.html

out/dist.dest/post/my-second-post.html

out/dist.dest/post/my-third-post.html

10.25.bashWe can then open the index.html in our browser to view the blog. Every time

you run ./mill dist, Mill will only re-process the blog posts that have

changed since you last ran it. You can also use ./mill --watch dist or ./mill -w dist to have Mill watch the filesystem and automatically re-process the

files every time they change.

10.5 Extending our Static Site Pipeline

Now that we've defined a simple pipeline, let's consider two extensions:

-

Download the

bootstrap.cssfile at build time and bundle it with the static site, to avoid a dependency on the third party hosting service -

Extract a preview of each blog post and include it on the home page

10.5.1 Bundling Bootstrap

Bundling bootstrap is simple. We define a bootstrap task to download the file

and include it in our dist:

build.mill10.26.scala-valbootstrapCss=link(-rel:="stylesheet",-href:="https://stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.5.0/css/bootstrap.css"-)+defbootstrap=Task:+os.write(+Task.dest/"bootstrap.css",+requests.get(+"https://stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.5.0/css/bootstrap.css"+)+)+PathRef(Task.dest/"bootstrap.css")

build.mill10.27.scaladefdist=Task:forpost<-posts()doos.copy(post.path,Task.dest/"post"/post.path.last,createFolders=true)os.copy(index().path,Task.dest/"index.html")+os.copy(bootstrap().path,Task.dest/"bootstrap.css")PathRef(Task.dest)

And then update our two bootstrapCss links to use a local URL:

build.mill10.28.scala-head(bootstrapCss),+head(link(rel:="stylesheet",href:="../bootstrap.css")),

build.mill10.29.scala-head(bootstrapCss),+head(link(rel:="stylesheet",href:="bootstrap.css")),

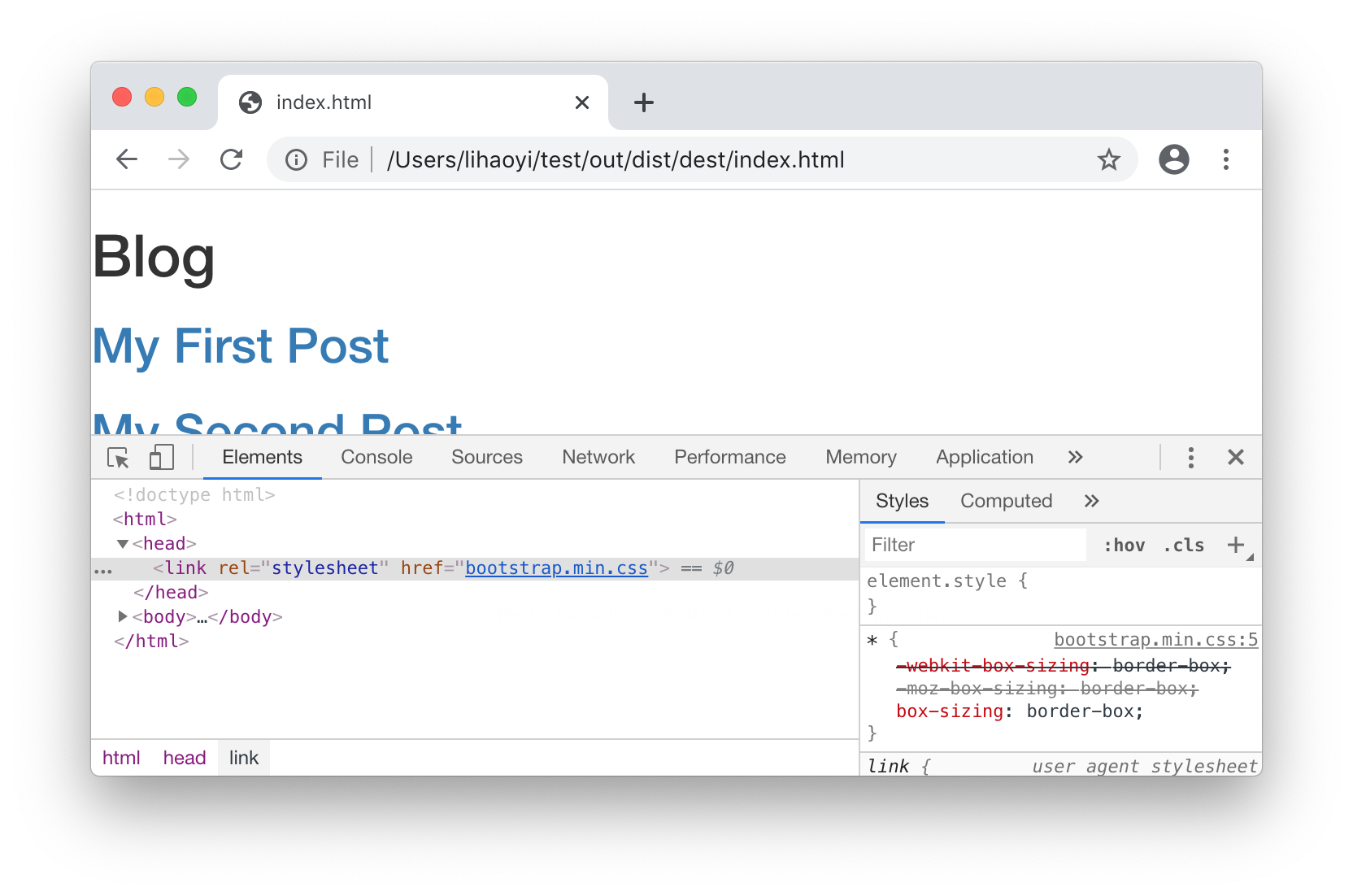

Now, when you run ./mill dist, you can see that the bootstrap.css file is

downloaded and bundled with your dist folder, and we can see in the browser

that we are now using a locally-bundled version of Bootstrap:

$ find out/dist.dest -type f

out/dist.dest/bootstrap.css

out/dist.dest/index.html

out/dist.dest/post/my-first-post.html

out/dist.dest/post/my-second-post.html

out/dist.dest/post/my-third-post.html

10.30.bash

Since it does not depend on any Task.Source, the bootstrap = Task: task never

invalidates. This is usually what you want when depending on a stable URL like

bootstrap/4.5.0. If you are depending on something unstable that needs to be

regenerated every build, define it as a Task.Input{} task.

We now have the following build pipeline, with the additional bootstrap step:

10.5.2 Post Previews

To render a paragraph preview of each blog post in the index.html page, the

first step is to generate such a preview for each PostModule. We will simply

take everything before the first empty line in the Markdown file, treat that as

the "first paragraph" of the post, and feed it through our Markdown parser:

build.mill10.31.scalatraitPostModuleextendsCross.Module[String]:defnumber=crossValuevalSome((_,suffix,path))=postInfo.find(_(0)==number)defpath=Task.Source(markdownPath)+defpreview=Task:+valparser=org.commonmark.parser.Parser.builder().build()+valfirstPara=os.read.lines(path().path).takeWhile(_.nonEmpty)+valdocument=parser.parse(firstPara.mkString("\n"))+valrenderer=org.commonmark.renderer.html.HtmlRenderer.builder().build()+valoutput=renderer.render(document)+outputdefrender=Task:

Here we are leaving the preview as output: String rather than writing it to a

file and using a PathRef.

Next, we need to aggregate the previews the same way we aggregated the

renders earlier:

build.mill10.32.scaladeflinks=Task.Input{postInfo.map(_(1))}+valpreviews=Task.sequence(postInfo.map(_(0)).map(post(_).preview))defindex=Task:

Lastly, in dist, zip the preview together with the postInfo in order to

render them:

build.mill10.33.scala-forsuffix<-links()-yieldh2(a(href:=("post/"+mdNameToHtml(suffix)))(suffix))+for(suffix,preview)<-links().zip(previews())+yieldfrag(+h2(a(href:=("post/"+mdNameToHtml(suffix)))(suffix)),+raw(preview)// include markdown-generated HTML "raw" without HTML-escaping+)

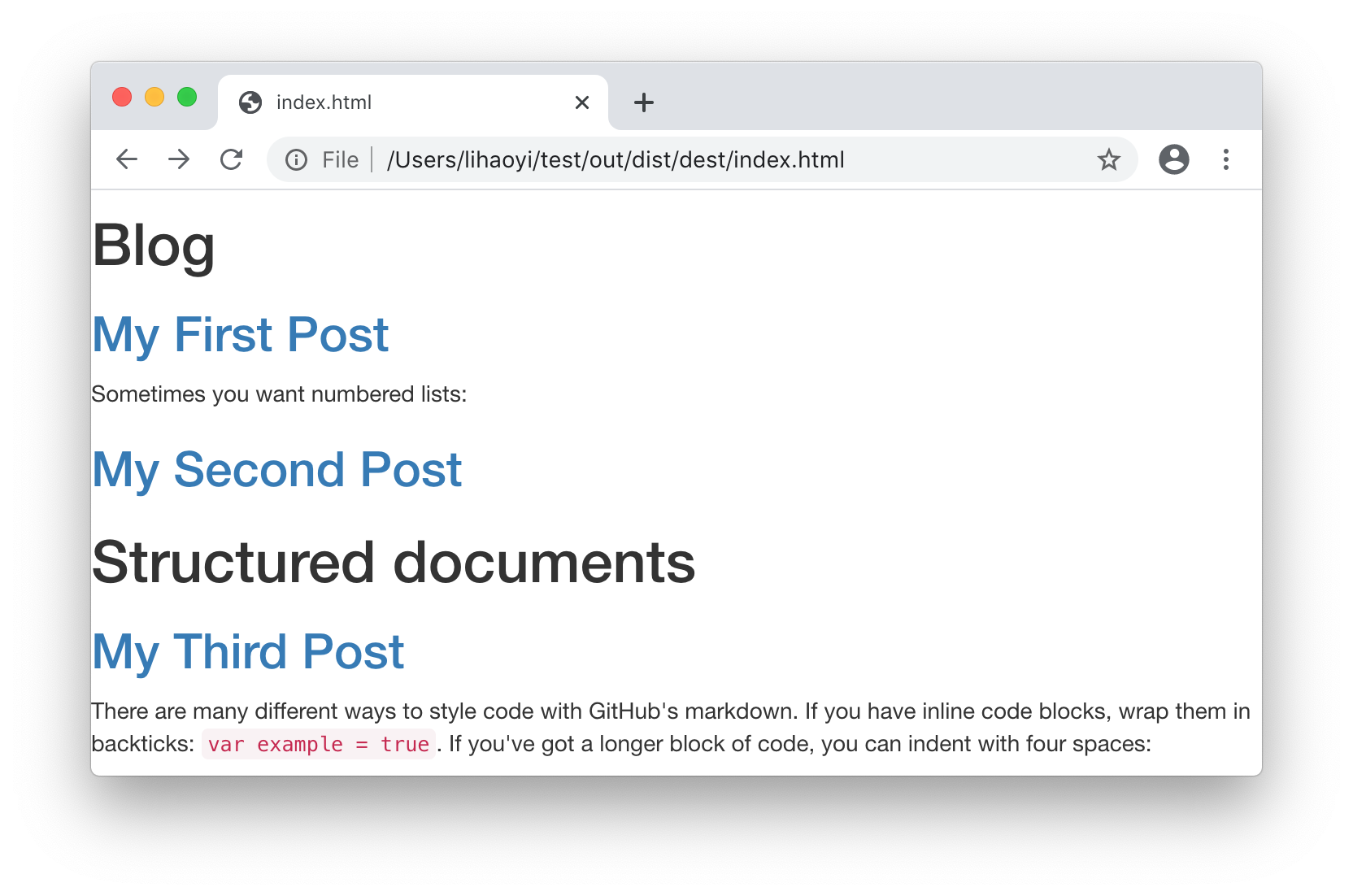

Now we get pretty previews in index.html!

The build pipeline now looks like:

Note how we now have both post[n].preview and post[n].render tasks, with

the preview tasks being used in index to generate the home page and the

render tasks only being used in the final dist. As we saw earlier, any

change to a file only results in that file's downstream tasks being

re-generated. This saves time over naively re-generating the entire static site

from scratch. It should also be clear the value that Mill

Modules (10.2) bring, in allowing repetitive sets of tasks like

preview and render to be defined for all blog posts without boilerplate.

10.5.3 A Complete Static Site Pipeline

build.mill10.34.scala//| mvnDeps://| - com.lihaoyi::scalatags:0.13.1//| - org.commonmark:commonmark:0.26.0importmill.*importmillBuildCtx.api.importscalatagsText..all.*defmdNameToHtml(name:String)=name.replace(" ","-").toLowerCase+".html"valpostInfo=BuildCtx.watchValue:os.list(BuildCtx.workspaceRoot/"post").map:p=>vals"$prefix-$suffix.md"=p.last(prefix,suffix,p).sortBy(_(0).toInt)defbootstrap=Task:os.write(Task.dest/"bootstrap.css",requests.get("https://stackpath.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.5.0/css/bootstrap.css"))PathRef(Task.dest/"bootstrap.css")defrenderMarkdown(s:String)=valparser=org.commonmark.parser.Parser.builder().build()valdocument=parser.parse(s)valrenderer=org.commonmark.renderer.html.HtmlRenderer.builder().build()renderer.render(document)defrenderHtmlPage(dest:os.Path,bootstrapUrl:String,contents:Frag*)=os.write(dest,doctype("html")(html(head(link(rel:="stylesheet",href:=bootstrapUrl)),body(contents))))PathRef(dest)objectpostextendsCross[PostModule](postInfo.map(_(0)))traitPostModuleextendsCross.Module[String]:defnumber=crossValuevalSome((_,suffix,markdownPath))=postInfo.find(_(0)==number)defpath=Task.Source(markdownPath)defpreview=Task:renderMarkdown(os.read.lines(path().path).takeWhile(_.nonEmpty).mkString("\n"))defrender=Task:renderHtmlPage(Task.dest/mdNameToHtml(suffix),"../bootstrap.css",h1(a(href:="../index.html")("Blog")," / ",suffix),raw(renderMarkdown(os.read(path().path))))deflinks=Task.Input{postInfo.map(_(1))}valposts=Task.sequence(postInfo.map(_(0)).map(post(_).render))valpreviews=Task.sequence(postInfo.map(_(0)).map(post(_).preview))defindex=Task:renderHtmlPage(Task.dest/"index.html","bootstrap.css",h1("Blog"),for(suffix,preview)<-links().zip(previews())yieldfrag(h2(a(href:=("post/"+mdNameToHtml(suffix)))(suffix)),raw(preview)// include markdown-generated HTML "raw" without HTML-escaping))defdist=Task:forpost<-posts()doos.copy(post.path,Task.dest/"post"/post.path.last,createFolders=true)os.copy(index().path,Task.dest/"index.html")os.copy(bootstrap().path,Task.dest/"bootstrap.css")PathRef(Task.dest)

10.6 Conclusion

In this chapter, we have learned how to define simple incremental build pipelines using Mill. We then took the script in Chapter 9: Self-Contained Scala Scripts and converted it into a Mill build pipeline. Unlike a naive script, this pipeline allows fast incremental updates whenever the underlying sources change, along with easy parallelization, all in less than 90 lines of code. We have also seen how to extend the Mill build pipeline, adding additional build steps to do things like bundling CSS files or showing post previews, all while preserving the efficient incremental nature of the build pipeline.

Mill is a general-purpose build tool and can be used to create general-purpose build pipelines for all sorts of data. In later chapters we will be using the Mill build tool to compile Java and Scala source code into executables. For a more thorough reference, you can browse the Mill online documentation:

This chapter marks the end of the second section of this book: Part II Local Development. You should hopefully be confident using the Scala programming language to perform general housekeeping tasks on a single machine, manipulating files, subprocesses, and structured data to accomplish your goals. The next section of this book, Part III Web Services, will explore using Scala in a networked, distributed world: where your fundamental tools are not files and folders, but HTTP APIs, servers, and databases.

Exercise: Mill tasks can take also command line arguments, by defining def name(...) = Task.Command{...} methods. Similar to @main methods in Scala files, the

arguments to name are taken from the command line. Define an Task.Command in

our build.mill that allows the user to specify a remote git repository from

the command line, and uses os.call operations to push the static site to

that repository.

Exercise: You can use the Puppeteer Javascript library to convert HTML web pages into

PDFs, e.g. for printing or publishing as a book. Integrate Puppeteer into our

static blog, using the subprocess techniques we learned in Chapter 7: Files and Subprocesses, to add a ./mill pdfs task that creates a PDF version of

each of our blog posts.

Puppeteer can be installed via npm, and its docs can be found at:

The following script can be run via node, assuming you have the puppeteer

library installed via NPM, and takes a src HTML file path and dest output

PDF path as command line arguments to perform the conversion from HTML to PDF:

const puppeteer = require('puppeteer');

const [src, dest] = process.argv.slice(2)

puppeteer.launch().then(async function(browser){

const page = await browser.newPage();

await page.goto("file://" + src, {waitUntil: 'load'});

await page.pdf({path: dest, format: 'A4'});

process.exit(0)

})

Exercise: The Apache PDFBox library is a convenient way to manipulate PDFs from Java or

Scala code, and can easily be added as a dependency with --dep for use with Scala CLI REPL

or scripts via the coordinates org.apache.pdfbox:pdfbox:2.0.18. Add a new task to our

build pipeline that uses the class

org.apache.pdfbox.multipdf.PDFMergerUtility from PDFBox to concatenate the

PDFs for each individual blog post into one long multi-page PDF that contains

all of the blog posts one after another.